… What is our place and purpose in the universe? How did we arrive at something rather than nothing? Where are we heading? These are questions that lay at the center of every spiritual tradition. Since the beginning of the Scientific Revolution, Copernicus’s heliocentric model has shifted the way we think about our spatial orientation in the universe. Our feelings of centeredness and self importance have been pulled out from under us; only to leave the cold concrete floor of Modernity. Lyotard’s (1979) description of a postmodern era is partly characterized by skepticism toward meta-narratives. This skepticism toward all-encompassing narrative knowledge shifts our view of the universe away from a sense of centeredness, yet again. The egocentric perception of ourselves is threatened when we realize grand theories of a benevolent omnipotent creator fail to recognize the disorder and chaos within a vast universe. Our sense of feeling lost increases with the realization that the ‘True’ teleological value of the universe may never be uncovered. It is in this era, the wayward wanderer, lost in this eternal moment, must fight the great spiritual war. Constructed mental purgatories of dualistic thinking must be dissolved by letting go of hope and replacing it with will, replacing transcendence with imminence, and replacing nostalgia and salvation with presence. Without this shift in consciousness the great depression of our lives will prevail.

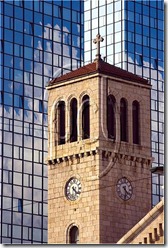

The Modern era of the West can be characterized by the centeredness of the individual and preoccupation with reason in a world made for the purposes of humans (Taylor, 1984). The idea of a sovereign God has been replaced with the sovereign self. This dualistic Master Slave relationship between the sacred and the profane has not been subverted, but rather inverted (Taylor, 1984). In this way, we remain slaves to our limited consciousness which continually tries to acquire a self through the acquisition of objects, while putting up walls of segregation from those who pose a threat to the ‘self’. Rampant capitalism reflects this shift toward the centered subject. Weber’s (1959) Protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism, illustrates the shift in religious discourse toward individualization, personal autonomy, the use of material gain as the source of salvation in what he describes as the “protestant ethic”. Many people now find themselves seeking refuge from this hurricane of economic preoccupation. The problem occurs when one realizes there is no place to turn in this illusion of a society, where the sacredness of the church itself is under threat. Before the rise of modernism the crucifix on top the church steeple was the highest point in the city and therefore representing the power of the divine (Levitch, 2002). Compare this to the high-modernist sky-scraper which towers above the grid plan representing the power of capital. Miller (1991) begs the question:

And where is there room for God in the city? Though it is impossible to tell whether the great cities have been built because God has disappeared, in any case the two go together. Life in the city is the way in which men have experienced directly what it means to live without God in the world.

The classic notion of “centeredness” is turned upside-down when the former center, God, is replaced with humanity (Taylor, 1984). Many world religions once considered direct experiences of the divine most sacred. This often consisted of orgiastic drug induced states of ecstasy (Weber, 1920). Rationalist influenced Christianity broke connection to these direct experiences, and maintained social stratification through its focus on hierarchy and sacrament. (Weber, 1920). This function of the church mirrors the economic sphere since it strives to maximize capital. Spiritual capital becomes the copyright commodity of the church: violators are prosecuted. The church capitalizes on this sense of lack: lack of purity, lack of wholeness, and ultimately the lack of God in the everyday experience of the city.

With the transition from Medieval symbolism of analogical participation, toward modern poetic symbolism of reference at a distance, the image of God had largely shifted from imminence toward distant transcendence by the 18th century (Miller, 1991). The modern symbols binding humans to God leaves humanity disconnected, isolated, and separate from God and the world itself. Miller (1991) calls this disconnect “spiritual poverty”. This alienation of spirit mirrors Marx’s (1964) notion the alienation in the workplace. This impoverished subject is left with a void that must be filled by consumption and through acquisition of objects (Taylor, 1984). This filling of the hole is an attempt to make the subject whole in order to produce a temporary measure of euphoria. This preoccupation with the commodity, the modern version of orgiastic ritual, takes the place of the divine. The commodity becomes a fetish and takes on a transcendent quality in the minds of the consumer (Marx, 1990). Furthermore, the commodity works within the modern economic system not only to keep the subject alienated from itself and the producer, but also works to keep the religious institutions full of longing followers seeking grace.

The idea of finite linear history, in the Christian sense, keeps the subject nostalgic for what has been, and looking forward to what has yet to come. Beginning... middle… end… between the ‘tick’ of Genesis and the ‘tock’ of the apocalypse, the history of the west runs its course” (Taylor, 1964). This anticipatory nostalgic state can be called the “unhappy consciousness” (Taylor, 1984). Satisfaction in this state is constantly delayed since the past and the future can never be the present. Comte-Sponville (2007) describes this same phenomenon as “cheerful despair”. He explains this state of despair as the following:

“You can hope only for what you do not have. Thus, to hope for happiness is to lack it. When you have it, on the other hand, what remains to be hoped for? For it to last? That would mean fearing its cessation, and as soon as you do that, you start feeling it dissolve into anxiety… with or without God – the hope for tomorrows happiness prevents you from experiencing today’s. (Comte-Sponville, 2007).

The unhappy subject becomes immersed in the anxiety laden consciousness of the perceived imperfection of what is, against the idealized, what ought to be. (Taylor, 1984). The lack of fulfillment leads to a sense of guilt and desire to revolt against the self. This existential dilemma is the inability of the I to live with the self. This is often expressed by the subject uttering, “I can’t live with myself”. Viewing this dilemma in light of Sartre’s (1943) concept of “bad faith”, the relationship of the I to the self can be imaginary and self-deceiving. The ‘sinner’ must realize that deceiving oneself with this identity results in unnecessary self-inflicted guilt. In this sense, hell is merely a self inflicted state of mind constructed by the Church and internalized by the individual. Rather than hoping for better days, the individual must actively participate in the eternal moment through the use of one’s will. Hope is the passive version of will, since willing something to occur requires one to take action (Comte-Sponville, 2007).

The Modern era can also be characterized by the rise of humanistic atheism. For the humanistic atheist, traditional values are turned upside in the attempt to convert “lovers of god” into “lovers of man”. This worship of reason is not sufficient since it does not question the function of truth, and the value of value (Taylor, 1943). The same insufficient ontological proof which is used in reference to the existence of God, is insufficient in proving that truth is the product of reason. This kind of proof is the atheistic humanist inverse of nothing more than an empty tautology (Marx, 1975). With the death of God, comes the death of the self. For the modern humanistic atheist, nihilism becomes the crucifixion of selfhood (Taylor, 1943). For this reason, one must look beyond both types of rhetoric.

“Since there is no transcendental signified to anchor the activity of signification, freely floating signs cannot be tied down to any single meaning” (Taylor, 1943). The realization that God has been born of, and died as a result of humanity, calls into question the legitimacy of religious authority as a whole. There are various reactions to the death of God ranging from those who are disinterested, those who are troubled by the implications of modernism and postmodernism on theology, in addition to those who take the illegitimacy of traditional authority with great enthusiasm. For instance, “like servants released from bondage to a harsh master or children unbound from the rule of a domineering father, such individuals feel free to become themselves (Taylor, 1984)”. It is the space between the belief and unbelief that the wanderer makes its way. This wanderer finds itself like Kafka’s character K:

“…haunted by the feeling the he is losing himself or wandering into a strange country, farther than ever man had wandered before, a country so strange that not even the air had anything in common with his native air, where one might die of strangeness (Harman, 1988).

Levitch (2002) expresses that, “to be completely lost in ones consciousness is to know precisely ones place in the universe. We are vagabonds in the eternal. Language is but a process of signification that will always fall short of representing the real; since it is the world of words that creates the world of things in which the signifier can never fully grasp the true essence of the signified (Lacan, 1957). In this way, language is always imperfect; therefore, capturing the absolute in language is absurd. The absurdity of the absolute and the loss of our spatial orientation in history do not necessarily mean one must throw spirituality by the way-side. Rather, “the aimlessness of serpentine wandering liberates the drifter from obsessive preoccupation with the past and future” (Taylor, 1984). Such liberation provides the key to spiritual practice that is based on the universe rather than God, the world rather than the Church, and experience rather than faith. In this way, traditional Christian theology is largely challenged by this conception of a postmodern shift in consciousness. As well, the sovereignty of reason has shown its limitation. Lawlessness is the new grace that only arrives when God and self are dead and history is over (Taylor 1984).

The dilemma of existential meaning can now go beyond the binary codes of language that have plagued modern Christian theology. The death of dualism allows the absolute to be conceptualized as Epicurus's pan, Lucetius's summa summarum, and Spinoza's nature: necessarily all conditions, relationships, and points of view (Comte-Sponville 2007).

Kafka’s The Castle can be interpreted as a modern depiction of alienation within bureaucracy, and the futile quest for an unavailable God. This is motif of an unsuccessful explorer as opposed to a stray wanderer. The explorer with a goal feels incomplete if the goal is not met, while the wanderer accepts the absurdity of the search and feels at home in all locations. This is the death of hope and the acceptance of what is. Taylor (1984) illustrates this in the act of sauntering:

To saunter is to wander or travel about aimlessly and unprofitably. The wanderer moves to and fro, hither and thither, with neither fixed course nor certain end…having forsaken the straight and narrow and given up all thought of return, the wanderer appears to be a vagrant, a renegade, a pervert – an outcast who is irredeemable by law… erring is serpentine wandering that comes, if at all, by grace – grace that is mazing.

The very fact of mere existence as opposed to non-existence is why-less. In asking why a flower blooms, we are confronted with a host of contingencies that take us into eternity. Interdependence in this web-like why-less absurd universe is the mystery that cannot be put into words or explained away by any kind narrative. Comte-Sponville (2007) claims that in the face of reality, silence of sensation and attention are more appropriate than attempting to dispel the mystery. He relates this to the silence of prayer and meditation without an object. In Beckett’s (1952) Waiting for Godot,Vladimir and Estragen have the following conversation which illustrates the absurdity of their endeavors:

Vladimir: I’m curious to hear what he [Godot] has to offer. Then we’ll take it or leave it.

Estragon: What exactly did we ask him for?

Vladimir: Were you not there?

Estragon: I can’t have been listening.

Vladimir: Oh… nothing very definite.

Estragon: A kind of prayer.

Vladimir: Precisely.

Estragon: A vague supplication.

Vladimir: Exactly.

Estragon: And what did he reply?

Vladimir: That he’d see.

Estragon: That he couldn’t promise anything.

Vladimir: That he’d have to think it over.

They are not only waiting for something that never comes, but the waiting itself is damnation: “Waiting is the final loosing game” (Cavell, 1969). Suspended in history, waiting for salvation or damnation is damnation in itself. The void must be used for one’s own purpose, rather than be void of purpose (Carvell, 1969). Beckett’s (1952) Waiting for Godot is not a play demonstrating the meaninglessness of life, but rather that emptiness is not a state, it is an infinite task which calls one not to protest against the emptiness, but rather, to see what one is filled with (Carvell, 1969). Becoming must appear justified at every moment, without requiring reference to the past or the future (Taylor, 1984). The experience of being is above and beyond the banality of what is – it is beyond explanation and out of empirical reach (Comte-Sponville, 2007).

Lucky’s speech in Beckets (1952) Waiting for Godot gives insight into the shrinking nature of humanity as we discover our extreme insignificance within the vast universe:

…but time will tell |to shrink and dwindle / fades away| I resume Fulham Clapham in a word the dead loss per |caput / head| since the death of Bishop Berkeley being to the tune of one inch four ounce per |caput / head| approximately by and large more or less to the nearest decimal good measure round figures stark naked in the stockinged feet in Connemara in a word for reasons unknown no matter what matter the facts are there…

Beckett references Bishop Berkley, the idealist whose views on immaterialism consist of God as being the cosmic all-perceiver (Kroll, 1995). Beckett explores whether the cosmic observer is neglecting to pay attention to his creation. This metaphysical question, for Beckett, is the inverse of Bishop Berkeley's belief that God is benevolent and attentively omnipresent (Kroll, 1995). Opposed to Berkley’s beautiful and harmonious view of the universe, Beckett sets the scene with Vladimir and Estragon in a universe plagued by disjunctions which suggests that God's detachment has become so noticeable that it seems as if God is virtually powerless (Kroll, 1995). Lucky’s references of ‘shrinking’ and ‘dwindling’ may represent the shrinking of humanity’s significance as the world is imagined within an infinity of space. Not only is the shrinking of humanity seen, but the shrinking of Gods role in the minds and everyday experience of people. Comte-Sponville (2007) takes a materialist view of this shrinking phenomenon when he describes it as the following:

“We are in the universe, part of the All or of nature. And the contemplation of the immanency that contains us makes us all the more aware of how puny we are. This may be wounding to our ego, but it also enlarges our soul, because our ego has been put in its place at long last. It has stopped taking up all the room.

Spirituality in the materialist sense consists of living and experiencing as opposed to seeking supernatural transcendence. God is not in nature like water to a sponge, but rather is nature; therefore, instead of using the word 'God', the word 'nature' is sufficient. Spirituality of immanence cannot be given, attained, or bought. It is not magic or God given, but rather, an inner experience. The Jewish tradition calls it 'the breath of life', the Christian tradition calls it being 'filled with spirit', and the Buddhist tradition calls it 'being awake' (Comte-Sponville, 2007). The spiritual life must lead followers down the path of intimacy and connectedness with the richness of being, rather than alienating individuals from themselves and from other religious traditions. It is through this breaking down of dualistic and religious barriers that our sense of at-one-ness with all that exists may emerge. Freud (1929) used this term “Oceanic Feeling” in Civilization and its discontents when referring to limitlessness, eternity, and feeling of wholeness which is experienced when the boundary between ego and object is lost, blurred, or distorted. Although this experience is not intrinsically equated with religion, it is often described with religious language. Dr Jill Bolte Taylor (2009) in her book My Stroke of Insight illustrates the oceanic feeling in her description of having a stroke which temporarily impaired the functioning of her left brain hemisphere:

I felt as if I was trapped inside the perception of a meditation that I could neither stop nor escape… As the language centers in my left hemisphere grew increasingly silent and I became detached from the memories of my life, I was comforted by an expanding sense of grace… In this void of higher cognition and details pertaining to my normal life, my consciousness soared into an all-knowingness, a 'being at one' with the universe... I no longer perceived myself as a whole object separate from everything. Instead, I now blended in with the space and flow around me.

The body is characterized by the natural flow of “eating, drinking, pissing, shitting, and fucking” (Taylor, 1984). Without these bodily flows of substance in, substance out, our body would be lifeless like a deserted city sitting like a set of bare bones on a dusty plain. The eyes of a proper ‘straight’ world have been averted from such bodily flows of life which are seen as vulgar to the city. The modern city’s grid-plan is a monument to the ideals of progress, efficiency, and linear thought which are on display for the corporate executive looking out onto this skilled attempt to become ‘civilized’. Even within this machine, the human spirit will not be caged. One may easily wander through the city, flabbergasted to be in the presence of such life. Wandering by foot is the chosen method of the saunter to lose one’s self amongst the cities flow: life’s flow. “Time and space of graceful erring are opened by the death of God, the loss of self, and the end of history. In uncertain, insecure, and vertiginous postmodern worlds, wanderers repeatedly ask: ‘Whither are we moving?’…” (Taylor, 1984).

When the dominoes of theological deconstruction fall into an eternal abyss, the question of what is the role of religion still stands. If religion will survive under the scrutiny of the postmodernist gaze it will need to re-open the book. The sacred book of Christianity has been left far behind by the wanderer in the infinite mirror maze of the library. The modern humanistic atheist may claim the library is not infinite, but is mistaken because they have merely stepped in front of the mirror and can only see a reflection of themselves. Stepping aside, one will realize the infinite reflection of signifiers which shows the library can never be complete.

Many people enjoy the fun house [or mirror maze] so long as they are convinced that there is an exit. Such people believe the book prescribes a cure. The nausea that vertiginous uncertainty creates is settled by the promise of certainty… [but] the only thing more disconcerting than uncertainty is certainty. A world in which every person has a number on his or her forehead is not a world in which there is no fun; it is a world plagued by oppressive despair. (Taylor, 1984).

As a result of lacking an absolute transcendent signifier, language and the book are open into the eternity in which meaning is ambiguous: appearing and disappearing at the threshold of interrelated perspectives (Taylor, 1984). In this way the words of the pages will never fully capture the essence of what is signified. This imperfection can perhaps act not only as a metaphor to the human condition, but as a metaphor to the condition of the chaotic universe(s) as a whole. Letting go of hope to allow for acceptance may be the only way for the wanderer to obtain a temporary measure of grace in a time where God is dead…

___________________

References:

Beckett. S, (1952). Waiting for Godot. 1st English edition. Grove Press.

Cavell, S. (1969) Must we mean what we say?. Cambridge University Press. United Kingdom.

Comte-Sponville, A.(2007). The Little Book of Atheist Spirituality. Viking. New York.

Freud , S.(1929). Civilization and its Discontents. London: Penguin, 2002

Harman, M. (1998) The Castle, Schocken Books, New York, New York,

Kroll, N. (1995). Berkeley inside out: existence and destiny in 'Waiting for Godot'. The Journal …………of English and Germanic Philology.

Lacan, J., The Function and Field of Speech and Language in Psychoanalysis in Écrits (1957)

Levitch, T. (2002). Speedology: Speed on New York on Speed. Context Books. 2002

Marx, K. (1990) Capital, Volume I. Trans. Ben Fowkes. London: Penguin, 1990.

Marx, K. (1975). Marx/Engels Collected Works. International Publishers. Vol 1, pg 683-685.

Marx, K. (1964) Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, New York City, International …………Publishers.

Miller, J. (1991). The disappearance of God: five nineteenth-century writers. The University of …………Illinois Press.

Sartre, J (1943). Being and Nothingness.Washington Square Press edition

Taylor, J. (2008). My stroke of insight. Plume; 1 edition. 2009

Taylor, M. (1984). A Postmodern A/theology. University of Chicago Press. 1984.

Weber, (1959). Weber, Max The Protestant Ethic and The Spirit of Capitalism. Dover …………Publications. 2003.

Weber, M. (1920). Sociology of World Religions. http://www.ne.jp. April 18th 2010

No comments:

Post a Comment